Greetings, gentle reader. In these dark times (* gestures toward…everything), we could all use a little fun. So if you, like me, enjoy Jane Austen’s novels and if you, like me, also enjoy using Tarot as a storytelling tool, then may I present: the Major Arcana tarot cards, except all of them are characters from Jane Austen novels.

[DISCLAIMER: Spoilers for 200-year-old novels below. Also, the beauty of both tarot AND Jane Austen characters lies in the rich variety of interpretations inspired by each. There are a gazillion ways I could have cast this list. I welcome debate but not vitriol.]

(0) THE FOOL – CATHERINE MORELANd

The easiest card to assign! Young, good-natured, credulous Catherine Moreland of Northanger Abbey embodies The Fool’s optimism and willingness to dream without reservation. She may learn some unpleasant truths about the ways of the world throughout the novel (after all, she has no little dog nipping at her heels to remind her about that sharp cliff at her feet), but at the novel’s end her kindness and sweet nature remain intact. Catherine generally believes the best of people, and of life itself.

(1) THE MAGICIAN – ELINOR DASHWOOD

Am I biased because Elinor Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility is my favorite Austen heroine? Certainly. But Elinor is a woman of many talents, with the drive to practice and refine them. No matter what life throws her way, she gets shit done. Need to build a budget for your dramatically reduced household income? Elinor’s got it covered. Need a skillful work of art? Elinor can paint one for you. Need to wrangle a collection of ladies who steadfastly refuse to hear reason? That’s Elinor’s main role in life. Need a ride-or-die defender to shield you from the man who ruined your life? Elinor. Need someone to make obligatory small talk with obnoxious relatives and friends, so that you don’t have to? Elinor’s got you. She gives the most Magician energy of all Austen’s heroines.

(2) THE HIGH PRIESTESS – lady catherine

Okay, but hear me out on this one. As a more intuitive version of The Hierophant’s reliance on rules and structures, The High Priestess knows that the way her intuition tells her things should be, reflects the way things actually should be. This way of looking at the world suits Lady Catherine de Bourgh, everyone’s favorite villain from Pride and Prejudice. You’ll note I haven’t said that Lady C’s understanding of rules and hierarchies is factually correct, simply that she considers them as such. From the raising of chickens to the shelving of cupboards to Pemberly’s pollution levels, Lady Catherine gives advice from on high and believes with all her soul that her gut feelings can stand as absolute truth.

(3) The Empress – Elizabeth Bennet

Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennet reigns as more than the Empress of our hearts, and more than Austen’s most famous heroine. She embodies the energy of The Empress card by embodying all of the best qualities in a heroine: warmth, courage, affection, dazzling intelligence, and a determination to defend and protect those whom she loves. Vanessa Zoltan and Lauren Sandler have called Pride and Prejudice the first female superhero story, and I agree – the scenes in which Lizzie Bennet fends off both Mr. Collins and (especially) Lady Catherine de Bourgh make us cheer for a reason.

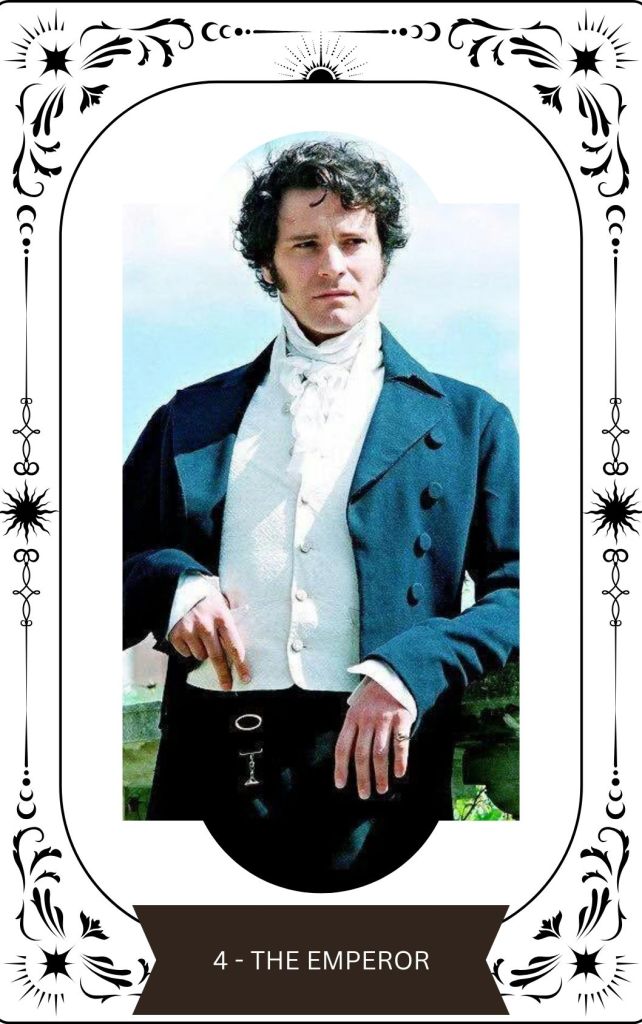

(4) The Emperor: Fitzwilliam Darcy

Obviously, right? Darcy not only exudes wealth and power, but his attractions for Elizabeth increase dramatically once she begins to learn just how competent he is at managing an entire county. Once she learns how caring and considerate a landlord Darcy has always tried to be, what a protective and affectionate brother he is, and what a tasteful homeowner he is? That’s super super sexy according to The Empress herself.

(5) The Hierophant – Edmund Bertram

Oh, our sweet and bland Edmund. I was determined that all of Austen’s leading men should appear on this list, and The Hierophant card’s energy feels most appropriate for Edmund. Clergyman Edmund possesses a warmth of affection for Fanny Price, but he also possesses a strict sense of propriety, of rules, of hierarchy, of responsibility, and of right and wrong. This quality makes it so frustrating (or, if you’re me, delightful) to read an entire novel in which he remains so deeply wrong about the woman on whom he crushes. The Hierophant can go one of two ways energetically: he can be a helpful guide and mentor, or he can be an annoying killjoy. For Fanny Price, Edmund gets to embody the first energy; for everyone else, the second.

(6) The Lovers: Anne Elliot and Frederick Wentworth

Look, I recognize that The Lovers will probably be the most contentious assignment of this entire post, and your mileage may vary. But when it comes to an immediate, consuming passion that transforms into long-term devotion, for which one is ultimately willing to sacrifice his pride and the other remains willing to sacrifice her lifestyle and place in society? After years? The honor goes to our favorite naval couple from Persuasion, at least for my money.

(7) The Chariot – Charlotte Lucas

The Chariot card is about seizing and/or maintaining control and momentum. Doubt her choice of life partner all you want, but Charlotte Lucas of Pride and Prejudice knows exactly what she wants, she makes a plan to get it, and she succeeds in her plan. Think of all of the variables she had to manage into smooth sailing: Mr. Collins’ wounded pride, Lizzie’s judgement, signing up for a life of feeling like second best and enduring a husband she cannot love. In today’s new age parlance, Charlotte Lucas manifests the hell out of her comfortable marriage and position with clear and determined eyes.

(8) Strength – Fanny Price

My choice in Mansfield Park’s Fanny Price may surprise those who simply view her as the most timid and milquetoast of all Austen’s heroines. But the Strength card relies less on outward courage and display of strength, and more on internal fortitude, which Fanny possesses in spades. I maintain my theory that when Austen sat down to write Mansfield Park, she sat down determined to write a heroine who is, among other distinctions, an introverted version of Elizabeth Bennet. Think about it: Fanny remains an observant and unerring judge of character, but rather than sharing her judgements as Lizzie does, Fanny keeps her observations to herself. As a young woman who starts her novel in the most disadvantaged position of all Austen’s heroines, Fanny has the farthest to rise in society and also the farthest to fall. Yet she remains steadfast in her adherence to right and wrong. She refuses to take part in the ill-fated Lover’s Vows production and steadfastly refuses to marry a man she cannot trust despite immense pressure (and eventual punishment) from her entire family, including her beloved and trusted Edmund. Even more impressive, she remains a kind and loving person after years of neglect from her family and years of outright abuse from Mrs. Norris. Now that is the Strength card personified.

(9) The Hermit – Anne Elliot

The Hermit card illustrates finding one’s truth in the quiet moments, and taking one’s own counsel. To me, Anne Elliot radiates that energy during the events of Persuasion. While she may have allowed Lady Russell to persuade her against her own inclinations and happiness as a teenager, nowadays Anne keeps no counsel but her own. Sometimes a hermit must wander off alone to explore her inner truth. Some hermits, like Anne Elliot, have mastered the art of wandering off alone for reflection even when surrounded by horrible other people. The more mature Anne Elliot of the novel thinks what she thinks and knows what she knows, whether she shares with others or not – and she’s almost always right.

(10) The Wheel of Fortune – Lucy Steele

Gotta hand it to Lucy Steele of Sense and Sensibility: the girl understands that life can throw curveballs, that fortunes come and fortunes go. This understanding makes up the essence of the Wheel of Fortune card. (A bit on the nose, Lucy literally rides a Wheel of Fortunes in the novel.) Whatever curveballs come, she will adjust and adapt, and do everything in her power to hold on to what’s hers and to what she believes she deserves in life.

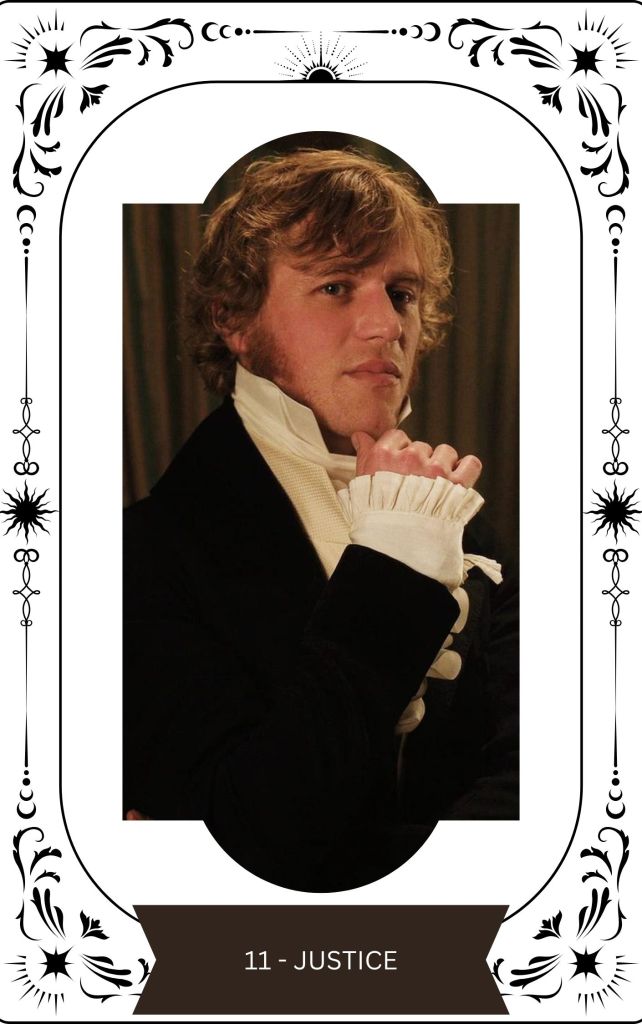

(11) Justice – George Knightley

Ah, finally we reach Mr. Knightley of Emma! Though perhaps not quite so impartial as he believes himself to be, at least not when it comes to a certain heroine, he is certainly the most levelheaded of the novel’s characters. Moreover, Mr. Knightley believes in fairness, in giving people credit where it’s due and calling out those whom he sees as unjust or dishonest (to witness: Mr. Elton, Frank Churchill, Emma, etc). He values Robert Martin’s inherent sense and goodness, and treats Harriet with kindness, despite differences in rank. He can’t stand to see a marginalized character like Miss Bates abused, however jokingly, by those of higher status. The Justice card suggests a call toward fairness and balance, and Mr. Knightley brings both to his respective Austen novel.

(12) The Hanged Man – Edward Ferrars

Sometimes you find yourself stuck in a situation, knowing that you’ve made your decisions and done all that you can without sacrificing your honor. Both the outcome and its timing now lie beyond your control – you have to ride it out and see what happens, like poor Edward in Sense and Sensibility. I’m not saying that Edward had zero responsibility for the awkward circumstances he now finds himself in…but I can’t help but pity him because they are extremely awkward. Even before the novel begins, Edward has already stranded himself in a life where he can only live in apprehension, waiting for the outcome of circumstances beyond his control. Once his secret engagement comes out into the open and he finds himself suddenly disowned, he must still live in apprehension about whether or not Lucy will set him free, how long it will take him to find a living as a clergyman, and so on. And while the engagement remains a secret, he has a chance to reconsider and revisit his circumstances through a different point of view – by comparing Lucy with Elinor. This opportunity for a change in viewpoint can also be suggested by The Hanged Man.

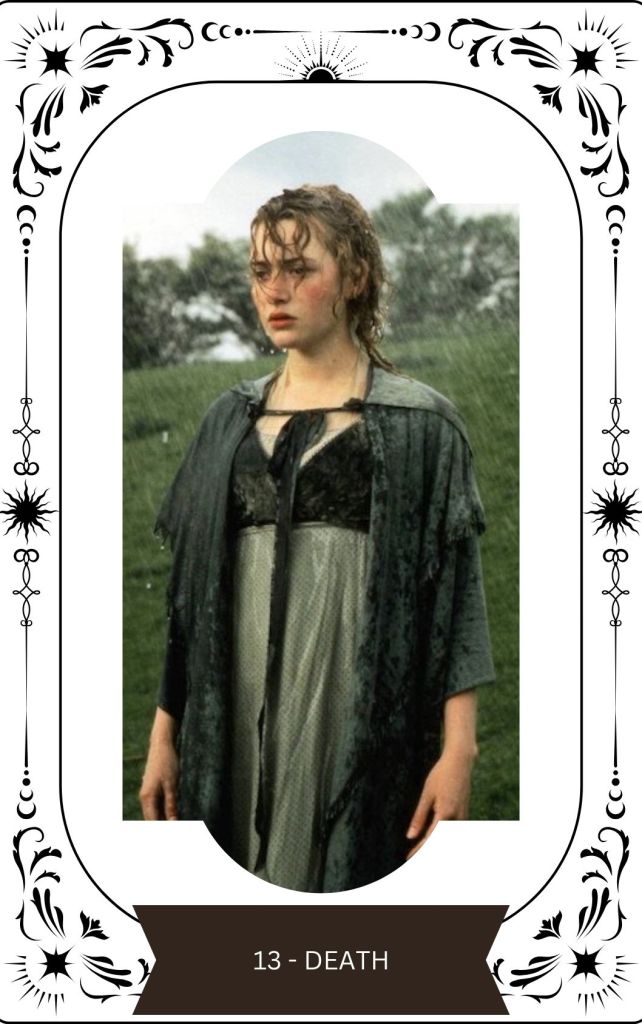

(13) Death – Marianne Dashwood

Famously the most misunderstood and misrepresented card in the deck, Death often refers less to physical death than to spiritual/mental rebirth: out with the old you, in with the new you and your new world. But Marianne Dashwood – the free-spirited, romantic, and impetuous younger heroine of Sense and Sensibility – has a story shaped by both types of death. Of all Jane Austen’s heroines, I find Marianne’s story to be the most drastic in its journey and character development. At the novel’s beginning, Marianne has constructed a very distinct identity and set of beliefs for herself, which she will relate to anyone who’ll listen (and even to those who won’t). By the end of the novel, the story and personality that Marianne prided herself on has come crashing down around her in the most painful and humiliating way – all that’s left to her is rebirth into a new, more composed, more mature version of herself. But Marianne’s journey is also shaped by two major encounters with physical death: her world changes dramatically for the first time following the death of her father, then once again after her own brush with death during her illness. She has not entirely changed as a character by the end – glimpses of the old Marianne still shine through – but her experiences have given her a new outlook on life.

(14) Temperance – Jane Bennet

Oh, sweet Jane. The Temperance card illustrates moderation and balance, and the oldest Bennet sister from Pride and Prejudice is nothing if not moderate and composed. (A little too composed when it comes to returning affection, it turns out. Charlotte Lucas isn’t wrong.) Her temperate energy reaches beyond her mild manner, however: during her discussions with the STRONGLY OPINIONATED Lizzie, Jane refuses to leap into anger or condemnation, always quick to remind Lizzie that explanations can and do exist somewhere between absolute villainy and absolute innocence. It’s easy to read Jane as a diffident foil for Lizzie, but read closely and you’ll realize that Jane more than holds her own against Lizzie when urging her to more moderate views. Lizzie might be more witty and irresistible, but Jane provides necessary temperance in their sisterhood and their family at large.

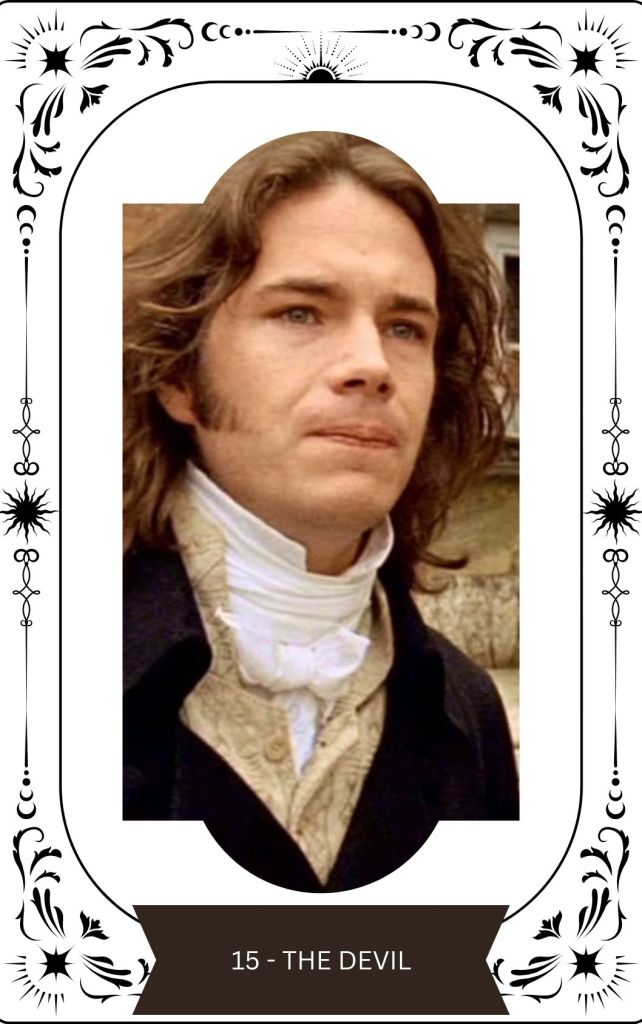

(15) The Devil – Tom Bertram

I tend to read this card not as representing an actual devil or similar villain, but rather representing a high-stakes struggle with temptation and vice. There were quite a few characters whom this card could fit (Wickham from Pride and Prejudice seems an obvious choice), but to me, Tom Bertram from Mansfield Park best represents the card’s element of struggle. From Chapter 3 onward, the eldest son of Lord Bertram exhibits a tendency toward alcoholism and other vicious pleasures which will hang over the rest of the novel like a cloud. His struggles materially impact not only himself but the rest of his family, particularly younger brother Edmund. Toward the end of the novel, they nearly cost him his life. Tom Bertram doesn’t seem like a bad person, but rather a careless person who tries and fails to wrestle with addictions starting at an early age.

(16) The Tower – John Willoughby

We’re more than halfway through The Fool’s journey now, and now we come to the terrifying Tower card. Sometimes, a bolt of lightning will hit the world that you have carefully built for yourself and send it crashing down around you. Sometimes that bolt of lightning is charming and well-spoken and hot, and is named John Willoughby. Just as the Death and Tower cards connect in their representations of dramatic change – one metaphoric, one catastrophic – Marianne and Willoughby from Sense and Sensibility are similarly linked. Marianne’s “death” and rebirth into a mature young adult could never happen without the catastrophe that is Willoughby, and Willoughby could never be such a catastrophe if Marianne wasn’t so much in need of maturation. But unlike Marianne, who learns and grows from her experiences and mistakes, Willoughby is just that bolt of lightning. By the novel’s end, he remains as selfish and careless as ever. (At least to me. You can argue that Willoughby repents his actions a tiny bit, but Austen herself points out that he ain’t exactly leaving his rich new wife to go right his many wrongs.)

(17) The Star – Mrs. Smith

The Star is one of my favorite cards in the deck. After our long night, the gauntlet run from The Hanged Man through The Tower cards, finally we can see a small but glowing light above us. Hope is renewed for a better outcome than we could first see in the immediate aftermath of our crisis. To me, no character in Austen illustrates such resilience better than Mrs. Smith, Anne Elliot’s childhood friend in Persuasion. Mrs. Smith has fought quite the bout with Deaths and Devils and Towers: after becoming a destitute widow when her beloved husband died and left her with his debts, she finds her options further restricted by a debilitating chronic illness. Nevertheless, following a brief period of despair, Mrs. Smith has found a new purpose in life, a new reason to get out of bed: enjoying delicious gossip. She refuses to let her difficult circumstances defeat her, instead exercising what Austen calls “an elasticity of mind” to rally and to find hope and amusement in her altered existence.

(18) The Moon – Frank Churchill

What the hell is Frank Churchill’s deal, anyway? You never quite know where you stand with him, or what he’s after. The king of double meanings and innuendos and playing all sides, Frank feels a bit of a cipher throughout most of Emma. Even once his secret engagement to Jane Fairfax is revealed, I just…why all the elaborate scheming, my dude? Did all your misdirections need to be quite so complicated? Before we can get from the hope of The Star card to the glory of The Sun card, first we must wade through the murky Moon card, which represents shifting sands, potential lies, and uncertainty. That pretty much sums up Frank Churchill.

(19) The Sun – Emma Woodhouse

For everyone who’s spent much of this list yelling “OKAY BUT WHERE IS EMMA?!” at me: here she appears, at long last! Finding a Major Arcana card for Miss Handsome, Clever, and Rich felt like an enormous challenge, but ultimately I feel that Emma embodies the most positive aspects of the Sun card. Sparkling presence, genuine and loving warmth, wealth and power and abundance – Emma carries all of these energies. And with the Justice-minded Mr. Knightley at her side making sure that she uses her powers for good, she simply shines all the brighter. We are happy, because she ends the novel genuinely happy.

(20) Judgement – Henry Tilney

We began our journey with Catherine Moreland as The Fool, and now we return to Northanger Abbey to finish the journey with Henry Tilney. I enjoy reading the Judgement card less as a monotheistic-Judgement-Day kind of judgement, and more as an internal calling: are you living as your best self? What do you feel called to do? My personal favorite romantic pair in all of Austen’s work, Henry and Catherine compliment one another by each inspiring a wake-up call within the other (much like that equally-excellent pairing, Lizzie Bennet and Mr. Darcy). When Henry quite literally judges Catherine for her flights of fancy and their potential harm, she feels called to acknowledge the wide gulf between imagination and real life going forward. When Henry, in his turn, learns how cruelly his father has treated Catherine, he feels called to stand up to his father by declaring his growing attachment to her. He immediately rushes to Catherine’s faraway home to offer her his hand in marriage. Happy sigh.

(21) The World – Col. Christopher Brandon

We made it! The World card represents the end of The Fool’s hopeful journey – or the end of this current journey, at least. The idea is to find completion in this round of personal growth, so that we can embark on a new journey equipped with all the life experience and self-knowledge we’ve recently gained. Colonel Brandon embodies so many facets of the World card. He has largely completed a Fool’s journey already (minus some lingering heartbreak) before Sense and Sensibility even begins, and he ends the novel ready to start a new phase of life, a new journey. Better still, he offers Marianne a chance to do the same, to enter a new phase of personal growth and a new chapter of her own life. The World can be read as a card of reward, and to me at least, Brandon is Marianne’s reward for the hard luck and humiliation that she has survived. I know there are plenty who disagree with me, who feel that Marianne is conversely used as a reward for Brandon’s friendship in a time of crisis. (And I can understand that point of view, especially since Austen herself writes the words “Marianne was to be the reward of all,” uggggh.) But Marianne also needs a new purpose in life, a new animating force, and I believe that she finds a loving and appropriate one in marrying Colonel Brandon – by allowing him to give her the world, har har. Brandon is a truly worldly character.

So, what do you think of our journey through the Major Arcana, reader? (Let us pretend we took said journey in a barouche.) How would you assign characters in your own deck?