[Oh my, look who’s posting for the first time in ages and ages! It me. That light at the end of the grad school tunnel finally approaches…]

It is a truth universally acknowledged that most Austen fans who read Northanger Abbey and find themselves wondering “What the heck is this Udolpho everyone keeps mentioning,” must subsequently find themselves running far from Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho as soon as they see it. Clocking in at 632 pages – and that’s with teeny tiny Penguin Classics type, mind you – Udolpho is a gothic monster most folks don’t mind skipping. Especially once they try to struggle through the first chapter or two.

Well, reader, Northanger Abbey has always been my favorite Austen novel and I finally decided to brave the monster myself. And here’s the thing: it’s not bad. It’s not exactly what modern readers would consider good, either, since editors have a lot more control these days – but once it got going I felt sucked in to the trashy fun, same as Austen and her family did a few years after its release. The fun is just wrapped in a whole lot of Romanticism and tiresome moralizing and endless nature writing.

Here are some thoughts in case you want to know the ways that Anne Radcliffe’s 1794 blockbuster influenced not only Jane Austen’s earliest (but last published) novel Northanger Abbey, but also Jane Austen’s writing style itself.

But first! Here’s a brief-as-possible plot synopsis (just kidding, this book is LONG.)

Emily, a virtuous young maiden growing up in the French countryside under the tutelage of her equally virtuous and conveniently wealthy father, enjoys the sublimity of the surrounding nature A LOT. Then her als0-virtuous mother dies. To rally her father’s spirits, Emily takes him on a tour across rural France, and they marvel over the sublimity of nature A LOT. One night they meet a wanderer named Valancourt, to whom both Dad an Emily take an immediately liking because he is likewise pure and virtuous because “he has never seen Paris.” They all enjoy the sublimity of nature A LOT. When they shelter near a mysterious castle (or chateau? whatever), Dad acts super cagey about his relationship to the castle and a woman who lived there long ago, then he promptly succumbs to illness and dies. Emily returns home, now under guardianship of an Aunt she’s never met.

Got all that? Good. 100 pages down.

Turns out Emily’s aunt is an awful person. She dithers on whether or not Emily should encourage Valancourt’s affections, finally setting up an engagement when she learns he’s from a wealthy family, because of course he is. Emily and Valancourt are very much in love and thrilled to get married except OOPS, Awful Aunt finds Even More Awful Italian Guy named Montoni, who talks her into marrying him, and Montoni immediately calls off Emily’s upcoming wedding. Valancourt is PISSED, but what can he do? Montoni also decides to whisk his new wife and “niece” off to Italy with zero warning, which is not a sketchy thing to do at all.

They get to Italy, where Emily appreciates the sublimity of nature A LOT. She is pursued by one Count Morano, whom she continually rebuffs, and Montoni forces her to marry the Count until OOPS he mysteriously whisks her and her aunt of to the remote castle property of Udolpho the night before the wedding. FINALLY WE GET TO THE GOTHIC GOOD STUFF. IT HAS TAKEN 216 PAGES OF MICROSCOPIC TYPEFACE TO GET HERE.

Time for some good ole fashioned Gothic horror! And it’s great stuff, too. Remember that glorious passage in Northanger when Henry Tilney teases Catherine about all the Gothic tropes she can expect to find once they reach the Abbey? All of that’s lifted straight from the Udolpho plotline. Here we have secret staircases for devious deeds, unsavory and criminal characters led by Montoni, a housekeeper named Dorothy who makes cryptic remarks, a heroine isolated from the rest of the family in a remote part of the castle, moans and supposed ghosts, eerie music from nowhere, and of course, a forbidden portrait in a haunted chamber, covered by that infamous black veil! (Spoiler alert: like Catherine, we will forever be guessing what’s behind that stupid black veil because Radcliffe NEVER, in 600 pages, tells you precisely what it is, just that it’s so horrific that Emily faints whenever she thinks about it. Talk about a tease.)

Montoni just wants his new wife’s money, and after she refuses to sign it over to him he deliberately neglects her until she dies. Then when Emily also refuses to sign the property she just inherited from her aunt over to Montoni, he essentially sets his band of outlaws upon her. At the last minute she’s rescued by ANOTHER handsome young man, who’s been in love with her for his whole life, but whom she’s never met, even though they were next door neighbors. Convenient, that.

Now all that’s left is for our Emily to reunite with Valancourt and live happily ever after, right? Wrong. Because we still have 200 FUCKING PAGES left, in which Ms. Radcliffe decides to introduce entirely new characters, including a young heroine named Blanche who is also virtuous and loves the sublimity of nature and why, oh WHY am I supposed to care about these people?! Anyway, they finally become connected to Emily’s story, and Emily finds out that Valancourt still loves her as much as ever, except unfortunately *GASP* he learned how to gamble while she was in Italy, and now she needs 100 pages or so to decide whether or not her virtuous heart can forgive him for, I don’t know, acting like a 20-year-old boy visiting Paris for the first time.

BUT! Before she finally forgives him, she learns that she’s the illegitimate daughter of her father and a marchioness who lived in the very castle Dad was sketchy about 500 pages ago, and that said marchioness was murdered by a woman named Laurentini, whose creepy portrait hung in Udolpho covered by a black veil. Also Laurentini’s a nun now. And she quickly dies after telling Emily all this. This lineage means Emily is ultimately related to the new characters we only got to meet 200 pages from the end, which, I mean, fine, whatever. And Emily FINALLY forgives Valancourt for having “seen Paris” and they finally get married and live happily ever after. The End.

So…yeah. That’s The Mysteries of Udolpho in the smallest nutshell I could manage. Here’s why this novel matters to us Austen fans, beyond enhancing our enjoyment of Northanger Abbey:

1. Sense of Humor

Even though Udolpho was published in 1794, 17 years before Jane Austen’s first book was published (although only six years before she wrote an early draft of Northanger), there is certainly kinship here. One can see, in Radcliffe’s writing, the seeds of Austen’s famously dry wit in skewering the self-satisfied upper classes, especially in passages featuring Madame Cheron (Emily’s aunt). Consider the moment where Udolpho’s narrative voice describes Madam Cheron as wearing

the blush of triumph, such as sometimes stains the countenance of a person, congratulating himself on the penetration which had taught him to suspect another, and who loses both pity for the supposed criminal, and indignation of his guilt, in the gratification of his own vanity. (p. 116)

Or this gem, after a gentleman mocks her: “Madame Cheron did not perceive the meaning of this too satirical sentence; and she, therefore, escaped the pain, which Emily felt on her account” (p. 122).

Or this delightfully Austenian moment:

“I will not be interrupted,” said Madam Cheron, interrupting her niece, “I was going to say – I – I – I have forgot what I was going to say.” (p. 120)

Austen’s obnoxiously talkative female characters, like Miss Bates from Emma or Mrs. Jennings’ daughter Charlotte from Sense and Sensibility or even Mary from Persuasion, also share DNA with Radcliffe’s servant characters in Udolpho, especially with lady’s maid Annette.

In such similarities we see the precursor not only to Austen’s incomparable talent for snarky insults, but also – nearly lost in the midst of a lot of ridiculous Gothic storyline – of Austen’s focus on the close relationships between women behind closed doors. As in Austen’s writing, the relationships and friendships and rivalries between women are given the most detailed character work in Udolpho. Men, by and large, are either suspicious or outright dangerous – even Emily’s beloved father harbors a dangerous secret.

2. Travel by Proxy

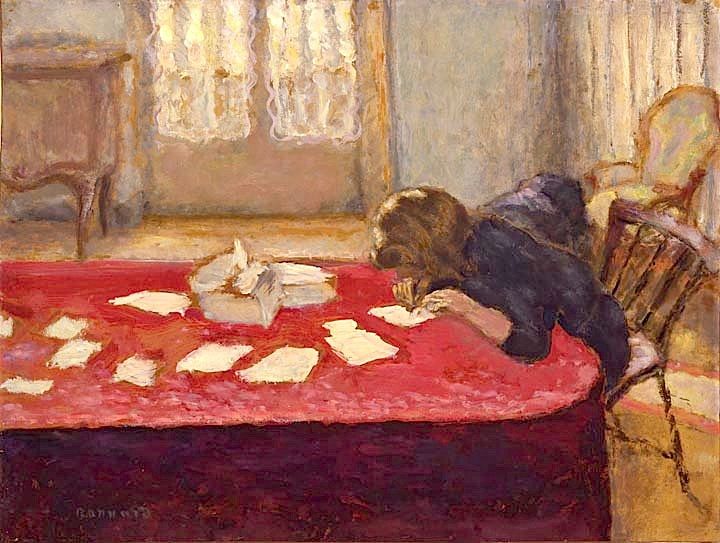

When Catherine, in Chapter 14 of Northanger Abbey, declares that the landscape outside Bath reminds her of “the south of France,” the moment is played mostly for laughs. When a bemused Henry Tilney realizes that Catherine has never actually been to France, but simply thinks of how Udolpho describes the French countryside, I believe we as readers are meant to feel bemused along with him. Here’s the thing, though: now that I’ve actually read Udolpho, I get what Catherine means. I’m not a terribly visual reader, unfortunately, but for those who are, I can see why this novel would be transporting. And I mean that literally – it took me many pages’ worth of frustration to catch on, but I finally realized that Radcliffe wrote The Mysteries of Udolpho to be half suspense novel, half travelogue. Emily’s journeys take her throughout the French countryside and the French Mediterranean coast, to Venice, and on to the wild mountains of Italy before returning her to her beloved French chateau, La Valle. I cannot emphasize enough how much Radcliffe describes each of these locations in excruciating detail – the sublimity of nature is subliming itself aaaall the fuck over this novel. This fact not only betrays Radcliffe’s Romantic sensibilities but also positions this novel as escapism of every kind for 1790’s readers. Beyond its sensationalist and propelling plot, Radcliffe’s writing allows readers to take a virtual vacation to France and Italy. For many women of this time period, a nice trip to the Continent was nearly impossible – and during the 1790s and early years of the 1800s, as the UK prepared itself for a supposed invasion by Napoleon, such travel was of course difficult and dangerous for basically everybody. For a girl of young Jane Austen’s social status, Udolpho was not only a gate to thrills and chills but also a gate to somewhere much more beautiful than the same sitting room at home in which one had to pass hours every day.

The travelogue trappings also gives Radcliffe permission to write her more salacious content, since said content supposedly occurred in a savage, medieval Europe, far way from “civilized” 18th-century England. As Henry Tilney says in his blithely imperialist chastisement of Catherine’s suspicious:

“Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions that you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember that we are English, that we are Christians.” (p. 186, emphasis added.)

Oof, British Imperialism.

The brilliance of Northanger Abbey, of course, is the way that Austen takes Radcliffe’s sensationalized European dangers and translates them for 1790s Bath.

3. Menfolk

While I note the similarities above between Radcliffe’s female characters and those of Jane Austen, it’s important to note just how differently these two authors view their menfolk. Of course we must keep in mind that Radcliffe set out to write a Gothic horror story, so that might go a long way toward explaining why nearly every man in the book represents some degree of physical danger or threat. (Well, except maybe for Ludovico and poor, sweet, friend zoned Du Pont). Even the lover Valancourt, in his more passionate outbursts, carries an element of unpredictable threat in his desperation. Can you believe this guy? Here’s a taste, upon their enforced separation:

“Emily!” said he, “this, this moment is the bitterest that is yet come to me. You do not – cannot love me – It would be impossible for you to reason thus cooly, thus deliberately, if you did. I, I am torn with anguish at the prospect of our separation, and of the evils that may await you in consequence of it; I would encounter any hazards to prevent it – to save you. No! Emily, no! – you cannot love me.” (p. 150)

Blergh. Aren’t we glad that “If I loved you less, I might be able to talk about it more,” was coming down the road in just a few more years?

Not to mention that every man in this entire story seems to be physically incapable of hearing/respecting a woman saying “N0.” Which, of course, is an idea that Austen will thoroughly explore later, especially in Mansfield Park.

And then there’s the complex but unrepentantly evil stepfather Signor Montoni, responsible for so much of Emily’s suffering. When Catherine suspects General Tilney of murdering his wife, she’s naturally inspired by the merciless and secretive Montoni in Udolpho. Yet though her fanciful fears about General Tilney – and about the secret stairways, buried human skulls, and other horrors she hopes to find to prove his guilt – comically turn out to be the figments of an overactive imagination, Austen has not finished yet with the Montoni/Tilney comparison.

The misogynistic Montoni’s motivations for his cruelty toward Emily, after all, revolve around his desire to enrich himself through her advantageous marriage; General Tilney forthrightly shares the same priorities. Montoni has a cruel temper; despite his over-the-top civilities to Catherine (at least while he thinks she’s rich), we can see that Tilney’s temper has traumatized all his children, Eleanor in particular. Ultimately, of course, Austen parallels the height of Montoni’s cruelty through a similar story beat in Northanger Abbey. When Emily refuses to sign her inheritance over to him, he calmly tells her that he will no longer give her any protection from the men in his house who, you know, have been making casual remarks about their intention to rape her. General Tilney doesn’t do something so exaggeratedly villainous (he is English, as Henry would remind us), but his greatest cruelty toward any character in the book must be turning an unaccompanied Catherine out of his house with zero notice, forbidding Eleanor to provide her with a servant to protect her on a long and multi-step journey home, and not even caring whether or not she has enough money to make said journey home at all.

This action of General Tilney’s is not only “uncivil,” but outright cruel and extremely dangerous. For a young woman in the late 1700’s England to travel over a hundred miles without a guide or protection posed an enormous risk from assault by unknown persons, especially strange men – Austen doesn’t belabor the point because that’s not her style, but anyone reading Northanger Abbey at the time would have equated General Tilney’s actions with the threat of sexual assault. In the end, then, Catherine is proven right. General Tilney really is Signor Montoni. Just not in any of the ways that she had enjoyed imagining. In her sendup of The Mysteries of Udolpho (and other popular gothic novels like it), Austen deliberately creates for us an 18th-century, British, respected-member-of-society Montoni. The dangers facing young women like Catherine and Isabella Thorpe might have their edges sanded off here, but Austen dials the comedy vibe down occasionally to remind us that those dangers, and the powerful men who control them, are no less serious or frightening.

4. The Endless Moralizing

Gah, just so, so much moralizing about virtue and vice and propriety and mental fortitude and spiritual fortitude and whatnot. It helps one appreciate Austen’s own moralizing: those who complain that Sense and Sensibility is too blunt in its moralizing would find it subtle compared to Radcliffe.

So there you have it. Believe it or not, I have more thoughts, but I think I should stop before I write a blog post as long as The Mysteries of Udolpho. Now go forth, and watch the BBC movie version of Northanger Abbey if you haven’t already!

Have you read Udolpho yourself and compared it with Northanger Abbey? What are your thoughts?

Citations from Penguin Classics paperback of The Mysteries of Udolpho by Anne Radcliffe. 2001: Penguin, London.

Essay copyright Kristin Hall 2023.