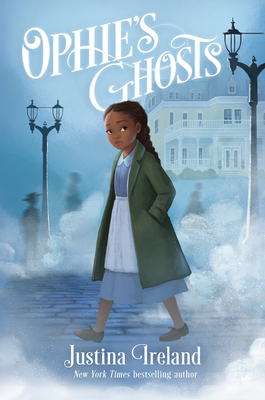

“It filled her with a sense of ease, and as they approached, she spun around, taking in the small part of Pittsburgh where it seemed that being a Negro was no more unusual than wearing a hat.”

Justina Ireland, OPHIE’S GHOSTS

[Note: this review covers an advance reader’s copy provided by HarperCollins.]

I’m always on the lookout for middle grade titles that discuss America’s racist history and/or present in ways that 1) don’t talk down to their audience and 2) won’t make readers feel like they’re in school. Ophie’s Ghosts, Justina Ireland’s middle grade debut that’s scheduled to come out in May, just joined The Parker Inheritance at the top of my recommendation list.

This book pulls no punches when it comes to the way black people were treated by white people – and sometimes by fellow black people – during the 1920s. But it wraps those punches in an intriguing mystery full of haunted houses, ghosts, and complicated characters. Basically: go order this one right now!

THE STORY

Twelve-year-old Ophelia has an unusual talent: she can see and interact with ghosts. She learns about this talent one night when it saves her and her mother from death at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan. Fleeing Georgia with no money and little hope, they find refuge crashing with relatives in the rapidly growing industrial city of Pittsburgh. Soon Ophie’s mother, desperate to move out of their relatives’ house, pulls Ophie out of school to begin working with her as full time house staff for the white and wealthy Caruthers family.

Unfortunately for Ophie, her job at the Caruthers mansion turns out to be waiting on the elderly, bed-ridden, and abominably racist Caruthers matron. Also unfortunately for Ophie, the mansion turns out to be haunted by its past — literally haunted, as in haunted by ghosts. The other black staff members are terrified of Mrs. Caruthers, and everyone keeps making hushed references to the woman who used to have Ophie’s position. When Ophie befriends a young female ghost in the attic who can’t remember how she died, it’s up to Ophie to uncover the truth.

THE BABBLE

I love that Justina Ireland establishes a whole set of rules and mythology for the afterlife, while never becoming so busy focusing on the ghost story that she allows us to forget both the casual and aggressive racism that Ophie and her mother face every day.

The mystery is a slow burn–one that younger children in the middle grade range might find a little too slow, honestly, but for more patient readers it’s worth the wait. I found myself constantly amazed by the number of dimensions of white supremacy and racism that this middle grade ghost story winds up addressing: not just overt “bad guy” stuff from the KKK members and Mrs. Caruthers, but also colorism, microaggressions, passing, segregation in the south versus the north, and so on. The sequence when Ophie attends the movies with Clara, and she finds herself gaping at an entire functioning mini-society filled with people who look just like her, was heartwarming and devastating at the same time.

That sequence soon also became incredibly creepy, as do most of the ghostly moments in this novel. The ghosts in this world are genuinely spooky.

One last observation: it might just be an accident of timing, but this is the second occasion in the past year when I’ve read an #ownvoices novel starring a BIPOC character, shortly after reading a novel with a similar theme/plot written by a white author. The first time this happened, I read Tracy Deonn’s Legendborn shortly after reading Leigh Bardugo’s Ninth House, both of which follow a female black student on scholarship to an elite college, where she joins an ancient secret society of wealthy students that abuse magic in order to reinforce their privilege. This time, I read Ophie’s Ghosts after reading Cat Winters’ The Steep and Thorny Way, a loose YA adaptation of Hamlet in which a black teenager – also named Ophelia, interestingly enough – tries to avoid the rise of the KKK in 1920s Oregon after seeing the ghost of her dead father. Both cases serve as excellent examples for why #ownvoices publishing is so important, because in both cases, the BIPOC authors brought different levels of nuance and different areas of focus to similar stories, themes, and explorations. I enjoyed both Ninth House and The Steep and Thorny Way, and I’m not ready to say that only members of marginalized populations should be “allowed” to tell stories about those populations (Winters in particular did a ton of research and involved sensitivity readers in her writing process). HOWEVER. These two recent cases perfectly illustrate why from now on, for every Ninth House that’s published, there’d better a Legendborn published (preferably two Legendborns). For every The Steep and Thorny Way, there needs to be an Ophie’s Ghosts. It’s up to publishers to make that happen, but it’s also up to us as readers — and, more importantly, as buyers — to hold publishers to the fire to make sure it happens.

Anyway, soapbox aside, Ophie’s Ghosts is fantastic. I hope teachers read it and incorporate it into their lesson plans – I think it’s a worthy successor to Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. Ophie makes an engaging, opinionated, sympathetic heroine from the first page, and the characters around her are just as detailed. It’s a unique approach to this important and all-too-relevant subject, written in a modern style.

RATING

* * * *

RANDOM BABBLE

[From here there be mild spoilers. Ye have been warned.]

- I know I said it above, but some of the ghost encounters are friggin’ creepy. Dining room lady? Creepy. That rose garden scene? SUPER creepy. Honestly, they might be a little scary for younger readers, but it will depend on the reader.

- A testament to how well Ireland immediately establishes this world, and these characters, and the stakes that impact them: I had tears in my eyes by the end of the prologue.

- The mystery about Clara is such a slow burn, yet I still didn’t see part of that final reveal coming. Props to Ireland for that.

- Ophie’s dream to be back in school is gutting, and I appreciate that Ireland incorporates child labor into this story. A great way to discuss how school wasn’t mandatory for all children in the U.S. until 1930, and wasn’t strictly enforced for many years.

- I thought Ireland did a skillful job of weaving the different ways that Ophie and her mother are processing, or failing to process, their grief about Ophie’s father throughout the story, without allowing that to overwhelm the story or their relationship.

- Oh yeah, in case I haven’t made this abundantly clear elsewhere: